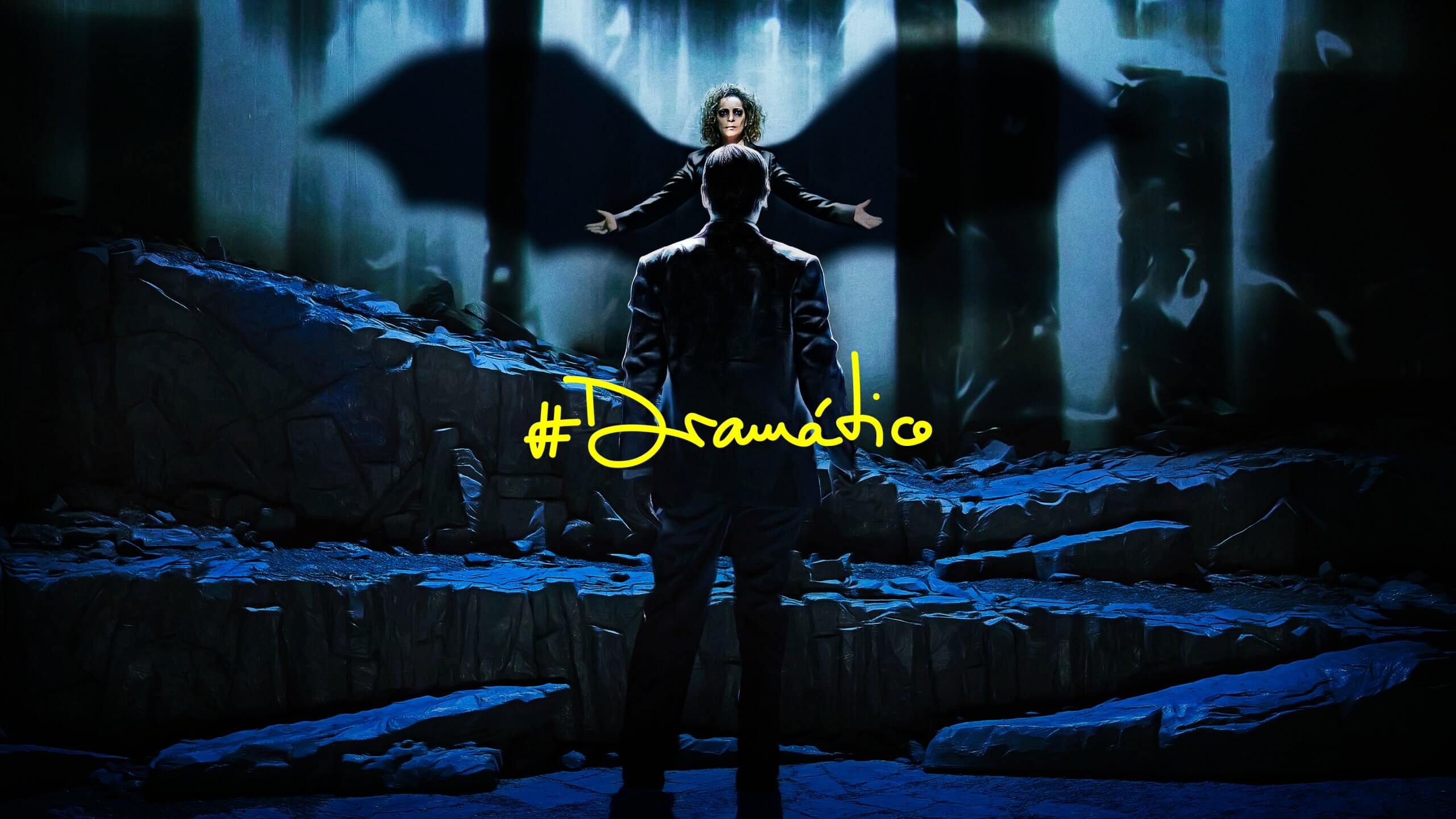

Synopsis

A tribute to the beauty of Milton’s words from a contemporary point of view, which is also a tribute to the profession of comedic actor, so often demonized for its capacity to transgress.

The epic poem published by John Milton in 1667 explains the tragedy of the fall of man, but also narrates the fall of Satan. Claimed by the romantics to be the true hero, Milton’s Satan symbolizes the rebel who rises up against the tyranny of heaven. Because before the fall of man there is the story of the fallen angel. The story of a failed rebellion and its consequences, which will determine the destiny of men and women. But, are we this way because our destiny was written that way or because our beliefs led us to write it that way? In addition to a celebration of the beauty of Milton’s language, this Paradise Lost also wants to build a tribute to the comedic actor’s craft, so often vilified, underestimated and demonized for its fascinating capacity for transformation and transgression. Comedic actors were not allowed to approach the cities, because it was feared that their trade could contaminate the people of good faith. The fear of knowledge has very old roots. “Can knowing be sin?” the serpent said to the woman. And it was the woman who chose knowledge rather than ignorance. But…

Director’s Note

A flap of wings, a flash of lightning, a thud on the ground, Satan writhes in pain. Pain is born. Satan rises up. Rebellion is born.

God and Satan, obedience and rebellion. Adam and Eve. These four characters star in this tale full of anger and fury, told by a blind man (Milton) that represents a considerable amount of our Western culture.

This staging is the attempt to understand our behaviour, to know if Faith is just a pre-conceived plan to ensure obedience; if spirituality is the intangibility of freedom or the perpetuation of fear.

In the review of our myths lie the eternal questions, the ones we have to keep asking ourselves: Who we are? How do I want to live? How do I face death? Paradise Lost, or the Bible, are books that we can believe in or books that we can interpret, like the most beautiful poetry. I was raised an agnostic, and I believe in the capacity of doubt. Satan challenges me today to ask questions of the one called God, creator, author. Today the theatre looks at itself in the mirror of myth, like the old ones. And John Milton, this immortal blind man leads us into this darkness. Because for those of us who do not obey, darkness is reserved for us. For those of us who believe that the apple, whether it’s from the witch in Snow White or the Devil, is very good. And the extraordinary original sin. And God knows it.

Andrés Lima

Author’s note

When I started writing the stage adaptation of Paradise Lost, I couldn’t have imagined that in a short time we were going to have to face an ocean of losses on so many levels. All of a sudden, everything was unexpected and inevitable, like in a good fiction story. But it was not fiction, it was reality. And a bad reality. Like the devil. The devil, they say, is bad. That’s how it’s always been presented to us. But it’s also useful. How useful to have someone who carries the epithet of evil. That allows others to appear better. More heavenly. That is also what Paradise Lost talks about. About power strategies. About the construction of an enemy.

Every rebellion begins with a failure. Re-bellum means to fight again. You have been defeated, you have fallen, but you get up and fight again. There are many who have tried, throughout history, to make the theatre disappear. But the theatre carries within it, like the fallen angel, the seed of rebellion. It’s always there, ready to get up and fight again. If there is any artistic profession that knows how to fall and get back up again, it’s the theatre. It’s that rebellious child who reminds us that we are not perfect. Perhaps now is a good time to ask yourself some questions about the beliefs that have been passed down to us. About its consequences in terms of the treatment of women, men, all living beings, the planet. Perhaps it’s time to listen to the words of the fallen angel. Before it’s too late to rewrite what we later call destiny.

In this theatrical adaptation, we give the audience the opportunity to feel part of each of the different tribes that face each other in the theatre space, a metaphor for the universe: angels, demons, actors, actresses, women and men. A trip to the place of the other, the opposite, the different, letting oneself go through Milton’s words and discovering what part there is in each one of us: angel, devil, man, woman, comedic actor or spectator.

Helena Tornero